This year will mark the 70th anniversary of the Great Patriotic War. It has particular significance for our nation as hundreds of thousands of Armenians fell in that war. If we take into account that in 1945 only 30 years had passed since the Genocide, which took the lives of 1.5 million Armenians, then it becomes clear how heavy the casualties our nation incurred during 1941-1945 were.

One of the consequences of this war was the emergence of German, Romanian, and Hungarian prisoners of war in Armenia. They were mainly engaged in construction works “redeeming” the sins of Nazi Germany.

Mediamax correspondent Anush Petrosyan found 87-year old Horst Howler, former prisoner of war (POW) of Kirovakan camp, in Berlin and talked to him.

- When and how did you take part in World War II?

- After I turned 16 in 1944, I was called up for military service as an assistant to air defense antiaircraft gun operating soldier. Back then there was lack of soldiers so many teenagers aged 16 were recruited as assistants to air defense soldiers. We were not even wearing German army uniform.

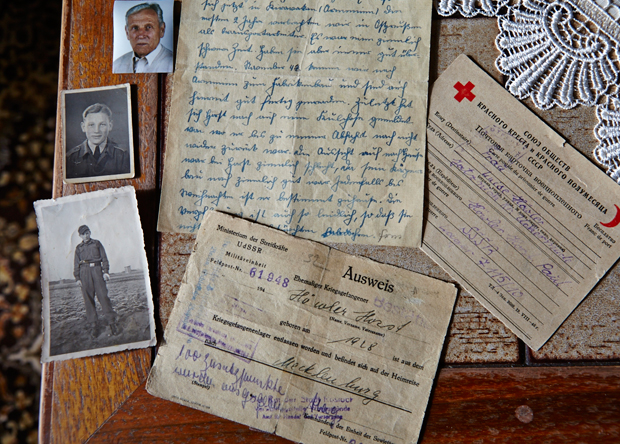

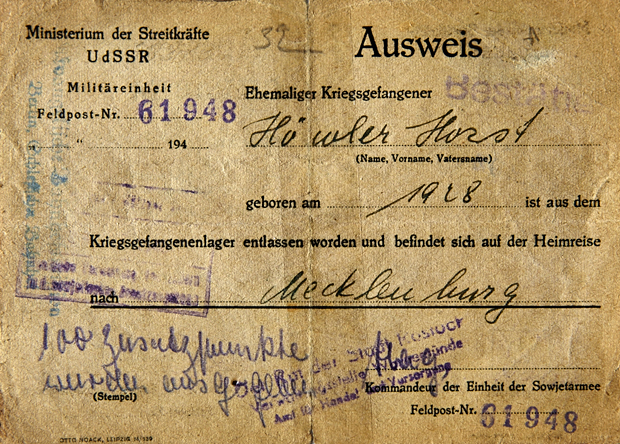

Horst Howler

Horst HowlerPhoto: from Horst Howler's archive

- How were you taken a war prisoner? It must be hard to be a prisoner of war, especially in such a remote and unknown country.

- The war had almost ended. It was May 7, 1945. The Soviet Army launched an offensive toward Germany from the Oder. We were taken during the escape. We had neither weapons nor any means to defend ourselves. We surrendered without battle. We first came to Konigsberg (now Kaliningrad) and in late December, 1945, we were taken to Kirovakan.

We thought we were being taken home, while it turned out we were moved far away from home. After three weeks on the road we arrived in Kirovakan. I know that now the name of the city has been changed to Vanadzor.

We were taken to Kirovakan camp for prisoners of war. At first we had no idea where we were.

- Violence and aggression used in the camps against the POWs are much spoken about. What do you remember?

-The guards was comprised of soldiers from various Soviet Union republics. They were guarding and accompanying us to work.

Photo: Nora Erdmann (www.noraerdmann.com) for Mediamax

The guards had varying attitudes to us and it was accounted by the emotional experiences they went through during the war. They were older and had their own war memories and practice. They had suffered much and had lost their family members and it is precisely why there was certain aggression toward the POWs. But now that I cast a glance back I realize that it couldn’t be otherwise. The soldiers who had lost their families and close ones because of the Hitler Army had to guard the POWs now. Naturally, they couldn’t treat us as nobles. We should understand that it was quite hard for them as well. There were lots of opposites. In part, the POWs were also causing troubles – they were sometimes acting aggressively in their claims and expressions.

Horst Howler

Horst HowlerPhoto: Nora Erdmann (www.noraerdmann.com) for Mediamax

Food shortage was a major issue back then; the Soviet Union was unable to provide food as there were no conditions. The USSR did not have enough food even for the children of the orphanage next to our camp. The population was also suffering from food shortage.

- Did you come into contact with the locals?

- I should say that we had good relations with Armenians but they were purely work-related.

During the first two years we were leaving the camp early in the morning and going to the building site with the guard. We were isolated from the population. We were communicating with only the Armenian builders who were controlling our work.

Besides, Armenians were speaking their own language, which was alien to us. I remember only a few Russian expressions we used to learn from the soldiers. I remember one of the most frequently used ones – “Oчень много работы” (“There is much work”). We used to hear Armenian but couldn’t get a word of it. I regret it much. There are few words I remember and one of them is «Շուտ արա» (Hurry up!).

Horst Howler

Horst HowlerPhoto: Nora Erdmann (www.noraerdmann.com) for Mediamax

In 1947-1948 we started getting some money as prisoners of war and along with that we got a chance to have an afternoon break. I remember the long street leading out from the camp with small sales outlets at the end. We used to buy sunflower seeds or tobacco from there. Our communication with locals was confined to only that.

During construction Armenians working with us used to give us bread or other things that we needed.

- What did you take with you from Armenia – things, friends, memories?

- I did not manage to take anything material. I was freed unexpectedly, within just a day. The guards took us to Tbilisi from where we finally reached home across the Black Sea coast.

I took only memories from Armenia and today they no longer seem to be holistic…

- Talks with your fellow POWs – don’t they complete your memories?

- Over many years, I tried to find the people with whom I was in the camp. But in vain, as I did not manage to find them I had only one friend from back then – he was freed earlier and went home earlier than me. We remained friends in Germany as well. However, he has already died.

Photo: Nora Erdmann (www.noraerdmann.com) for Mediamax

The rest were also gradually being released and were returning home. We did not manage to keep in touch. We lost each other. I lived in the German Democratic Republic where we hardly ever spoke about it. Besides, there was no institution where we could register and find each other.

The worst memory that remains is uncertainty. When we arrived in Kaliningrad as POWs, we had no clear information as to how long we would remain in captivity. It was redoubtable and ghastly.

We were taken to Armenia by train. It was cold winter. The road took three weeks. It was a sad, strained and complicated situation, which did much harm to the health. We had taken a cold and long road to uncertainty. We had no idea of where we were going and how long we would stay there. This uncertainty was scaring. The military officers of the Soviet Army were telling us that we were to recover all the losses the fascist war had caused. It was unbearable.

I was 17 back then. I was thinking “but what do I have to do with the Nazi war and damned Hitler?” I was not even a real soldier. I was taken a prisoner of war without committing any sin and did not feel even the slightest guilt for what had happened. I hadn’t done anything to the Soviet people. I had not fired even a single shot. Why was I to be a POW for four years, when I was not guilty at all?

But now that I look back over the years I realize that we had to take part of the guilt on us and claim responsibility and redeem it.

At my 87 I can say for sure that it was our duty as POWs to render modest support to the Soviet Union. I don’t have a sense of guilt but I neither find the decision the Soviet Union passed back then wrong. I think the young years of my life that I spent in captivity in Kirovakan do not spring up upsetting thoughts.

- Do you remember Kirovakan? Can you describe it?

- I know almost nothing about Kirovakan, We were in a camp in the center of the city. I remember crossing a river when going down for work. I think we were working on construction in one of Kirovakan suburbs to the north. We were building a factory under the supervision of Armenian specialists. They were dressing the red Armenian stone, cutting with their small hammers and turning them into squares. We were then taking the cut stones to the building site where the walls were being built. I was solely working on construction there and was helping the building constructors.

I thought quite much about it but never really managed to say where exactly in Kirovakan it was. We couldn’t go out in the city freely. We just knew the way to the building site and back “home.” People in my surrounding also tend to ask me about Kirovakan. Unfortunately, I don’t have much to say. I just know that our life was monotonous – camp-building site-camp.

Horst Howler

Horst HowlerPhoto: Nora Erdmann (www.noraerdmann.com) for Mediamax

One day in 1948 we were taken to work on a road. We were to make it wider. The road was stretching to Lake Sevan, people said. We worked on a mountain for weeks on end. Sometimes I talk to one of my acquaintances about Armenia. They all confidently say: “You must have courted many Armenian girls.” The wives of my sons joke saying: “Admit it. You surely have children in Armenia.” They do not understand that I really had a very monotonous life as a POW.

- What was your life like after you returned? Was there an adaptation period?

- Our train arrived in Frankfurt (Oder). My family and relatives were living in the Soviet territory – in German Democratic Republic (GDR). I also remained there. I lived with my mother in one of the small villages in Mecklenburg. At first it was unbearably hard – a curse. I was 21. Life in Soviet Germany was not easy at all. I jumped out of the frying pan into the fire where the situation of my relatives was not any better than mine as a former prisoner of war. The living conditions were hard and the quality of life was low but I managed to quickly recuperate. I learned shipbuilding and moved to Warnemunde. I worked in the shipbuilding sector for many years. I used to feel good in GDR. I should admit that although the situation was hard, I feel neither fear, nor fury when recalling the years of my captivity.

- How did that stage of life affect the further course of your life?

- You know, many Germany soldiers felt honored to fight, kill and struggle for their ideas. Captivity was unacceptable for them – it was better to be killed than to be taken prisoner. But I do not share this view.

Being a prisoner of war is not easy but being a POW is way better for a person’s inner world than having to deal with killing people on the front every day.

Horst Howler

Horst HowlerPhoto: Nora Erdmann (www.noraerdmann.com) for Mediamax

In this case, I personally preferred to be a war prisoner than take part in battle actions.

- What do you think about your life today and in the past days?

Photo: Nora Erdmann (www.noraerdmann.com) for Mediamax

- I am happy. I lead a “charmed life.” I live in Berlin with my 85-year old wife. I have a big family – my four sons, seven grandchildren and great-grandchildren adorn my life.

- Do you want to visit Armenia?

Horst Howler with his wife

Horst Howler with his wifePhoto: Nora Erdmann (www.noraerdmann.com) for Mediamax

- During the GDR I thought less about it. But now that I am much older and tried to put down my recollections for my family and friends, I thought that I should have gone to Armenia, Kirovakan. With age I attached more importance to my visit to Armenia, unfortunately I cannot fulfill that wish any more. I told my children only about the good moments of that period. I choose to keep the dark and hard parts to myself.

Anush Petrosyan talked to Horst Howler

Photos: Nora Erdmann, specially for Mediamax

Comments

Dear visitors, You can place your opinion on the material using your Facebook account. Please, be polite and follow our simple rules: you are not allowed to make off - topic comments, place advertisements, use abusive and filthy language. The editorial staff reserves the right to moderate and delete comments in case of breach of the rules.