80-year-old Lithuanian poet and translator Tomas Venclova is in Armenia 50 years on after his first visit to the country. Venclova translated Brodsky, Pasternak, Akhmatova, Baudelaire, Elliot, Prévert and many others into Lithuanian. His poems were translated as well - into English, Hungarian, German, Polish, Russian…

Tomas Venclova read out his poems for the first 40 minutes of the meeting, choosing the first and the last one to be in Lithuanian so that the audience could feel the sound of his native language, and read the rest in Russian. “I went to the wonderful Parajanov Museum today, and the director explained Parajanov’s collages. I’ll do something similar, although my poems are nothing like Parajanov’s collages,” the poet said, interrupting his reading for short comments.

The meeting was jointly organized by the Lithuanian Embassy in Armenia, Mirzoyan Library and Mediamax media company. The latter’s Director Ara Tadevosyan anchored the meeting.

America, the shelter of a dissident writer

I acquired anti-Soviet views after being influenced by the Hungarian Revolution. It was in contrast to my father, a Soviet poet. However, we managed to keep the loving relationship of father and son, which made me very happy. Everyone in Lithuania understood I was a different man, who wrote and thought differently. That was the reason I emigrated. I’ve lived in America for 40 years now. I worked for 30 years at a university. I was told I would miss it terribly when I retire. Unfortunately, I don’t miss it, although I worked with pleasure and the students liked me.

Your first translation is like your first woman

I started translating with Akhmatova’s works. It was my first experience of that kind, and I love her poems.

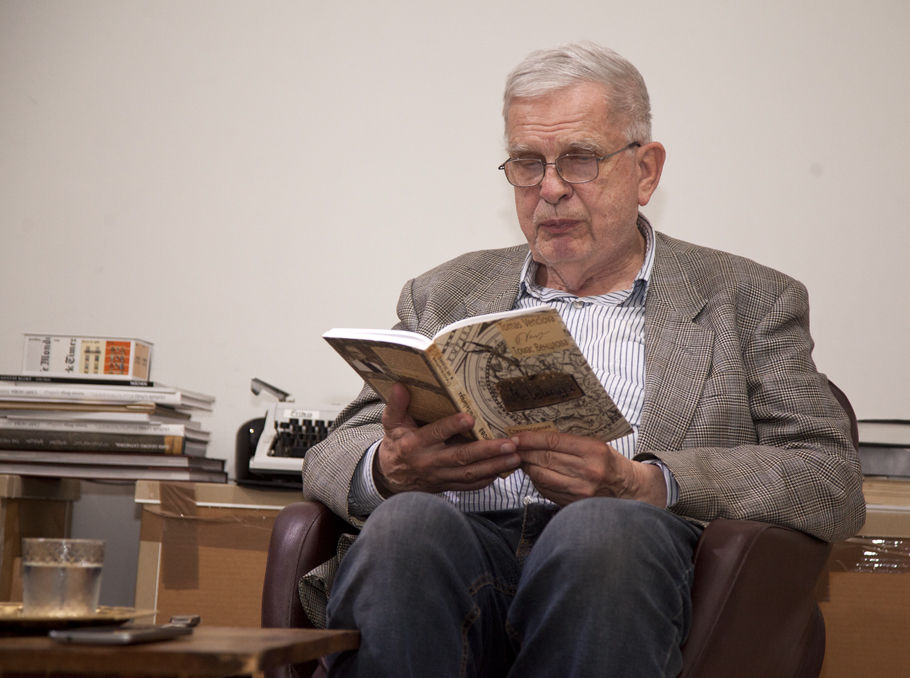

Tomas Venclova

Tomas VenclovaPhoto: Mediamax

The same as you never forget your first woman, you never forget your first translation.

Translation gives more joy than your own poems. With your own work, you feel its weak points and think that this or that part should have been better. Meanwhile, translation lives a life independent from yours. As uncomfortable as it is to say, sometimes you admire yourself and think that yes, bravo me, I did it. You feel very satisfied when you translate well. Your own poems don’t always give you that full satisfaction.

Difference between translation schools

There are two large translation schools, the Eastern and the Western. They now make interlinear glosses in the West. They translate the poem, constructed in a certain way, sentence by sentence. The final translation is correct, but it’s literal. It’s done in Lithuania now too. The other school is that of Pasternak, Marshak, and other great translators. They tried to create good poems in Russian, using the creative base of other writers. If the poet puts in great efforts or is a genius, that method works. The most important point is to make a good poem in your language and to show what kind of text is behind it.

The poet published in a “cultural city”

Once a Polish friend of mine wrote to me, saying he knew me as a poet thanks to translations of a great Polish poet. I replied immediately I guessed who the translator was, because there aren’t many great poets in the world. “Culture”, a periodical of great importance for Polish migrants, was published in Paris at that time, and Czesław Miłosz worked there. I asked my friend where my poem was published. I wrote to him that I thought it was in a certain “cultural city”, hinting to Paris and “Culture”. He understood me and responded with a yes, you’re right. That magazine was brought to me secretly later, and I felt like a knight. If Miłosz translates your poems, they must be worth something.

The story of "Lithuanian Nocturne"

Although it's noted that Brodsky wrote "Lithuanian Nocturne" in 1974, that's not actually true. He began writing that poem back in the Soviet Union, then abandoned it for a while and got back to it after moving to the U.S.

Photo: Mediamax

He called me quite often to clarify some details. In the poem, he commemorates Lithuanian pilots Darius and Girėnas, who flew from USA to Lithuania in 1933 and crashed in Germany. In particular, Brodsky asked if they were flying a monoplane of a biplane. When he finished the poem, he called me and read it out to me. Of course, I was very pleased that Brodsky dedicated such a poem to me.

Migration doesn’t kill a poet

More than half of Lithuania’s writers emigrated in 1944. Everyone was running from the Bolsheviks, because people feared they would come and things would end badly. They were probably right. Many people continued to write despite living outside of Lithuania. When I was leaving, I was afraid I’d stop writing, but I actually wrote no less in America, and I dare say, no worse than before. It was important for me to prove that you can still write while being a migrant and that it isn’t a tragedy for poets. Migration doesn’t necessarily kill a poet.

People will read and write poetry for as long as humankind exists

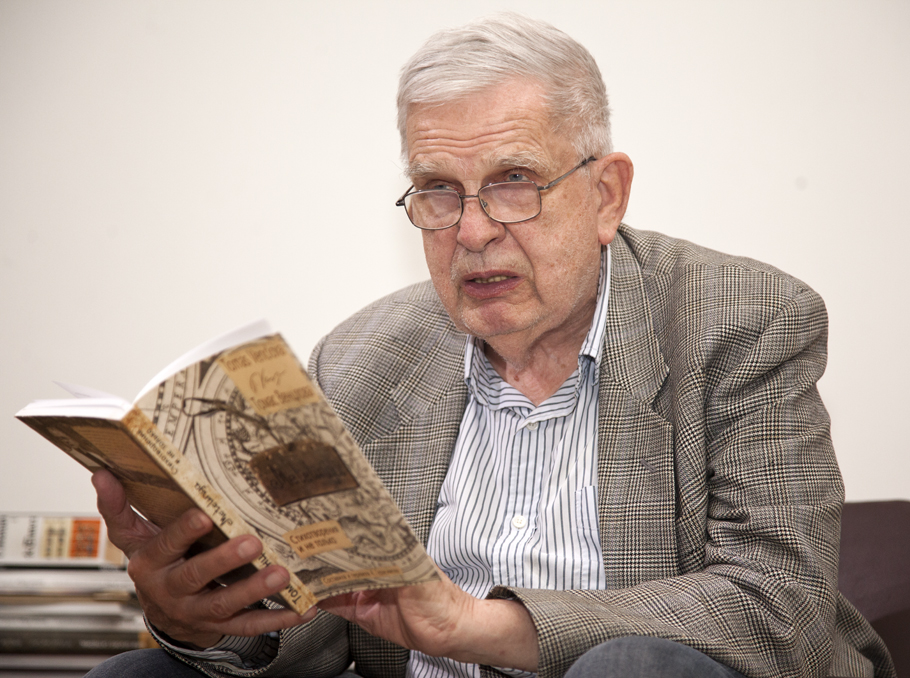

Tomas Venclova

Tomas VenclovaPhoto: Mediamax

Like many others, sometimes I get worried because it seems the new poets aren’t as good as those from my generation, and not only in Lithuania, but worldwide. I might be wrong. It seems to me that poetry is an art that will never die. Low tides happen and rising tides happen, the latter frequently colliding with bad times, and vice versa. There were many low tides in the history of poetry. I think it will all come back. People will read and write poetry for a long time, perhaps, for as long as humankind exists.

Lusine Gharibyan

Comments

Dear visitors, You can place your opinion on the material using your Facebook account. Please, be polite and follow our simple rules: you are not allowed to make off - topic comments, place advertisements, use abusive and filthy language. The editorial staff reserves the right to moderate and delete comments in case of breach of the rules.